Foundational reading skills have been getting a lot of attention lately.

Educators, parents, and legislators are all grappling with the reality that 69 percent 4th graders aren’t able to read proficiently and millions of American adults cannot read above a 6th grade level, and it’s swung the spotlight directly to the skills we expect most kids to master in 1st grade.

Those skills are called (you know where this is going, don’t you?) foundational reading skills, and they do just what their name describes. They provide a strong foundation or base for reading, which kids can then build on as they proceed through the upper grades.

But what does this all have to do with 4th graders who can’t read and adult illiteracy?

It turns out those same 4th graders whose reading scores are at the lowest levels also have “underdeveloped” foundational reading skills.

Ensuring very child has a mastery of these core skills is absolutely critical.

With that in mind, we’ve built an easy on-ramp to help you get up to speed quickly.

Read on for a comprehensive glossary including:

- Definitions of key vocabulary terms related to foundational reading skills and other reading instruction terms educators use when talking about building a strong reading foundation for students

- Examples of these crucial literacy skills in action

What Are Foundational Reading Skills?

Picture a baker building a multi-layer wedding cake without leveling off the bottom section or even allowing it to cool before piling on heavy layers of cake and frosting. Do you see a cakey mess in their future?

The skills we call foundational in literacy instruction are a bit like the bottom section of that cake.

Science of Reading research has proven that mastering foundational reading skills creates a strong base for future reading success, providing students with the tools they need to go from simply identifying alphabetic symbols by their letter name to reading fluently and deriving meaning from printed text.

When students have mastered these skills, they are able to:

- Read words

- Relate those words to oral language

- Read connected text (sentences and paragraphs) with the accuracy and fluency required to comprehend what they have read

What are the specific competencies that kids need to do all of this? Those skills all fall beneath five pillars of reading instruction that were identified by a National Reading Panel in the late 1990s. Sometimes called “the big 5,” they are:

- Phonemic Awareness

- Phonics

- Fluency

- Vocabulary

- Comprehension

Research shows there are lasting effects on students if they don’t master these skills in the primary grades. One in six students who aren’t reading proficiently in the 3rd grade will either drop out or not graduate from high school on time (a rate four times greater than that of proficient readers).

It’s not all doom and gloom!

Nearly all kids can be taught to read by the end of 1st grade — provided they receive evidence-based foundational literacy skills instruction — and students who achieve mastery of 1st grade level foundational skills like phonics are likely to still be on benchmark years later.

Foundational Reading Skills — Key Vocabulary

This list is in alphabetical order, so if you’ve got a specific term you’re curious to learn more about, feel free to skip ahead to that section of the alphabet.

Accuracy

The word accuracy may be familiar as a synonym for precision or correctness, but what does it mean in the context of teaching students how to read?

Reading accuracy is a measurement of how well a student reads aloud the words that are written in a text.

One popular measure of reading accuracy is words correct per minute (WCPM), a measurement that can be found by subtracting the number of mistakes a reader makes from the total number of words they have read, then dividing by the total time (in minutes) that it took to read a passage.

Alphabetic Principle

Teaching the letters of the alphabet is at the very foundation of reading instruction, but learning the “ABC’s” encompasses more complex skills than you might think.

Also known as letter-sound correspondence, the alphabetic principle can be defined as understanding that each letter has a specific sound or set of specific sounds and using that understanding to read and write.

The principle can be broken down into two distinct parts:

- Alphabetic understanding — Knowing words are made up of letters that represent the sounds of speech

- Phonological recoding — Knowing how to read and pronounce words accurately by translating the letters in printed text into the sounds they make

Automaticity

One of the goals of early reading instruction is to ensure students can read with automaticity, which means they have the ability to quickly recognize and decode words without effort.

When a student who has automaticity is presented with a passage of text, they are able to read the passage out loud, accurately pronouncing each word without having to decode the words.

In the early stages of learning to read, students with automaticity may still read slowly and without much expression. This is because automaticity is just one foundational reading skill among many, and students need to develop additional skills in order to understand the meaning of the words they’re reading aloud.

What automaticity does, however, is reduce the overall cognitive load on a reader’s brain. Because they can automatically recognize the word, their brain can shift to the mental work required to associate meaning to each word, reading more quickly, with expression and with an ability to comprehend.

Background Knowledge

Just as the name implies, background knowledge can be described as the information or knowledge that students already have about a particular topic.

When it comes to reading, this knowledge helps students understand what they’re reading, playing a key role in reading comprehension.

For example, if a student knows the word “ball” because they have played with the common toy, they have background knowledge of the word.

When this student encounters the word “ball” in a written text, their brain can call on this knowledge for help in decoding the word.

Consonant Blends

Sequences of two or more consonant sounds that appear together in a word are called consonant blends. Usually two or three letters, these elements of the English language are most commonly found at the beginning or end of a word.

In a blend, each consonant retains its individual sound, such as “br” in “bread” or “sl” in “slipper.”

Consonant blends are also sometimes referred to as consonant clusters or adjacent consonants.

Comprehension

Comprehension refers to the ability to make meaning from something. When we talk about comprehension in relation to reading instruction, there are two specific types:

- Language Comprehension — Language comprehension is the ability to understand both spoken and written communication in a particular language. It requires core skills such as vocabulary development, understanding the structure of the language and more.

- Reading Comprehension — Reading comprehension is specific to written communication, and it involves drawing on a number of skills to glean meaning, including understanding sentence structure, making inferences, drawing conclusions, and connecting prior knowledge.

Although both types of comprehension are related, there are key differences. Development of language comprehension needs to come first in order to lay the groundwork for reading comprehension or for students to derive meaning from text as readers.

Decoding

Decoding is the ability to recognize and read words out loud.

Because the English language is often described as a code that students need to crack in order to learn to read, decoding is considered one of the key foundational reading skills.

Students who are able to decode apply their knowledge of how letters correspond to individual sounds and how these letters work together to comprise words. This allows them to accurately read those words aloud.

This foundational reading skill is a form of bottom-up processing, which means students process printed text in order to glean meaning using different decoding strategies. Mastering decoding skills is a prerequisite for students to develop reading comprehension skills.

Digraph

A digraph is a combination of two letters that represent a single speech sound. There are two types:

- Consonant digraphs are made up of two consonants in a row such as the “sh” in “ship.”

- Vowel digraphs are made up of two vowels in a row such as the “ea” in “steak.”

Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills (DIBELS)

The Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, or DIBELS for short, is a curriculum-based measurement tool designed specifically to assess early literacy skills in students from kindergarten through 8th grade.

Developed at the University of Oregon, the DIBELS test measures a host of foundational reading skills from letter naming fluency to nonsense word fluency.

The literacy screener is a powerful benchmarking tool to understand where kids are in relation to critical benchmarks in service of learning to read on time. It allows schools and districts to understand how students are progressing from the beginning of the school year, to the middle, to the end of year.

DIBELS can also be used to determine whether or not the core curriculum is working or even identify pockets where it is working vs not working within a school system.

Encoding

If decoding is about discerning meaning from text, then it’s likely no surprise that encoding involves the opposite.

Decoding and encoding are like the two sides of the same coin.

Building off of letter-sound knowledge, encoding is the act of translating spoken words into written text — whether it’s individual letters, words or both. Both writing and spelling are examples of encoding.

Fluency

In reading, fluency refers to the ability to read with both recognition and comprehension.

Fluency is measured through six characteristics that can be observed when a student is reading aloud:

- Pausing — Strategically using brief stops or breaks

- Phrasing — Grouping words together into meaningful units or phrases

- Stress — Placing proper emphasis on certain syllables or words in a sentence

- Intonation — Conveying information about mood, attitude, and sentence type with the rise and fall of the voice

- Rate — Reading at a speed that’s appropriate for the content of the text

- Integration — Blending different linguistic elements (e.g., vocabulary and pronunciation)

Graphemes

A grapheme is a written symbol that represents an individual spoken sound, such as a letter or group of letters that make a particular sound when read out loud.

Graphemes can be individual letters such as <a> or <b>, but they can also be multiple letter units that work in tandem to create unique sounds such as <sh> or <ough>.

High Frequency Words

Sometimes referred to as sight words or heart words, high frequency words are commonly occurring words in written and spoken language.

These words are often taught via rote memorization, although literacy experts have shown that a phonics approach can be applied to sight words instruction.

Letter-Sound Correspondence

Also known as grapheme-phoneme correspondence, letter-sound correspondence is the relationship between the individual sounds in spoken words and the letters that represent those sounds.

For example, in the word “dog,” the letter “d” corresponds to the sound /d/ at the beginning of the word.

Understanding the relationships between letters and sounds is critical for students to become proficient decoders.

Mixed Reading Difficulties (MRD)

Mixed Reading Difficulties or MRD, is the term used to describe a reading disability that involves both decoding difficulties and comprehension difficulties.

Students with MRD often have trouble mastering foundational reading skills because they struggle with the sound structure of language and find it challenging to recognize familiar words quickly and accurately — both of which affect their decoding abilities.

Students with MRD benefit from targeted reading interventions which can be tailored to their specific needs.

Nancy Young’s Ladder of Reading and Writing

Nancy Young’s Ladder of Reading and Writing is an infographic that provides a visual representation of the varying levels of ease with which different children learn to read and write.

The ladder breaks these levels down into four distinct groups of students, based on decades of research into how different kids learn to read:

- 5-10 percent of students — Learning to read seems effortless; some instruction for spelling/writing may be needed

- 35-40 percent of students — Learning to read is relatively easy with broad instruction; some explicit instruction for spelling/writing likely needed

- 40-45 percent of students — Learning to read/spell/write proficiently requires code-based and explicit instruction

- 10 to 15 percent of students — Learning to read/spell/write proficiently requires code-based, explicit, intensive instruction and frequent representation

Dr. Nancy Young is a Canadian special education expert who designed the ladder to provide educators with a tool to guide them in differentiating reading and writing instruction to address the needs of all students.

Nonsense Words

Sometimes called pseudo words, nonsense words aren’t really words at all. These sequences of letters hold no real meaning, but they follow phonics rules, which makes them perfect for students to practice their decoding skills without relying on prior knowledge of real words.

For example, if a student encounters the nonsense word, “dake,” they can identify the “e” at the end of the word and apply the rule that tells them the vowel before the consonant — in this case the “a” in front of the “k” — will be pronounced as a long vowel sound.

Nonsense Word Fluency (NWF)

Nonsense Word Fluency or NWF is a literacy assessment that uses nonsense words to measure students’ knowledge of basic phonics and their understanding of the alphabetic principle.

Onset

The onset in a word is the initial consonant sound or sounds of a syllable before the vowel.

For example, in the word “cat,” the /k/ sound — represented by the letter c — is the onset.

Learning the onset in words helps students master the skill of matching sounds to letters when decoding words.

Oral Language

Oral language encompasses both speaking and listening skills — skills that children typically develop long before they begin traditional schooling. Oral language skills include understanding of the following:

- Phonological (sound) components

- Semantics (meaning)

- Syntax (grammar)

Researchers have found that students with strong oral language skills typically find it easier to learn to read than their peers.

Oral Reading Fluency (ORF)

Oral Reading Fluency or (ORF) is a literacy assessment metric that is used to measure a student’s ability to read words quickly and accurately, providing a measurement of a child’s reading fluency.

It is one of the most widely-used tools in education for measuring students’ foundational literacy skills, and it’s fairly simple to employ.

Students are provided with a grade-level passage and asked to read aloud from the passage for one minute while the instructor administering the assessment notes any errors they make. At the end of the minute, the total number of words read and the total number of errors are analyzed to determine the total words correct per minute or WCPM.

The assessment metric was originally created in the 1980s by researchers at the University of Minnesota. In the time since, University of Oregon researchers Jan Hasbrouck and Gerald Tindal have spent decades compiling ORF norms. Hasbrouck and Tindal used their research to create the standards upon which ORF assessments are now based.

Known as the Hasbrouck-Tindal oral reading fluency charts, these charts provide educators with the oral reading fluency norms for students by grade level. The chart breaks the normed data down further into intervals throughout the school year.

Orthographic Mapping

When students learn to connect the sounds they hear with the letters and graphemes they see, we call that process orthographic mapping.

For this to happen, the oral language processing part of the brain creates a mental map that links the visual symbols that make up written text with associated speech sounds. This map is then stored in the brain, ready to be called on when students encounter text, allowing them to recognize the letters and sounds automatically.

Orthographic mapping is not rote memorization of words. It’s a process that readers use to store information for easy recall.

Learning and applying phonics rules, for example, involves orthographic mapping. For example, if a student learns that the letters “fl” represent the consonant blend /fl/ and creates a mental “map,” they are then prepared to retrieve this information later when they encounter the word flag.

They will be able to recognize that the ‘fl’ in “flag” should be pronounced as /fl/, allowing for accurate pronunciation.

Phonemes

A phoneme is a specific speech sound that is created by a letter or a group of letters.

For example, both the /s/ sound made by the letter “s” and the /ch/ sound made by the letters “ch” when they appear together in a word are phonemes.

Because each phoneme represents a unique sound, the 44 different phonemes in the English language help us to distinguish different letters and words from one another.

These core components of the English language also play a key role in foundational reading skills development. Letter-sound correspondence instruction involves teaching pre-readers to associate each of these distinct sounds with corresponding letters or letter combinations, forming a foundation for decoding.

Grapheme is to encoding as phoneme is to decoding.

Researchers have proven that teaching students to segment phonemes in spoken words and identify their initial phonemes, as well as teaching them to recognize the graphic symbols that correspond to key sounds, is will help them acquire the alphabetic principle.

Print Concepts

Also called print awareness, the term print concepts describes the understanding of the elements of printed text, such as:

- Words are made up of individual letters.

- Sentences are made up of individual words.

- There are spaces between individual words in a sentence.

- Sentences begin with a capital letter.

- Sentences end with punctuation marks (e.g. period, question mark, exclamation point).

- In the English language, words are written left to right.

Prosody

Prosody refers to a student’s ability to read aloud with expression.

It encompasses a number of fluency characteristics, including reading accurately, pausing appropriately, putting the appropriate stress on words, and making use of rise and fall speech patterns.

Phonemic Segmentation Fluency (PSF)

Short for Phonemic Segmentation Fluency, the PSF is an assessment that is used to directly measure a student’s phonemic awareness. Students are assessed for fluency and their ability to segment spoken words into their components or individual phonemes.

R-Controlled Vowels

R-controlled vowels are vowels that are pronounced a specific way because they are followed by the letter “r” in a word. The “r” creates a unique vowel sound that is neither long nor short.

For example, in the word “car,” the vowel “a” is r-controlled. It doesn’t make a long “a” sound like the one in cake, nor does it make a short “a” like the one in bad.

Understanding this tricky phonics sound helps students with both reading fluency and spelling as they recognize and process these vowel combinations efficiently.

Rime

Maybe you’re having flashbacks to that college professor who made you read The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, or you’re just wondering if the literacy company spelled “rhyme” incorrectly.

The rime we’re talking about here is the part of a syllable that begins with the vowel and includes any consonant sounds that follow.

For example, in the word “map,” the “ap” portion of the word is the rime.

Teaching students to identify both the onset and rime in different words helps them learn the common chunks that are used in the English language, including various word families.

When a student can identify a rime, they can then apply this foundational knowledge to reading and spelling other words that contain the same rime.

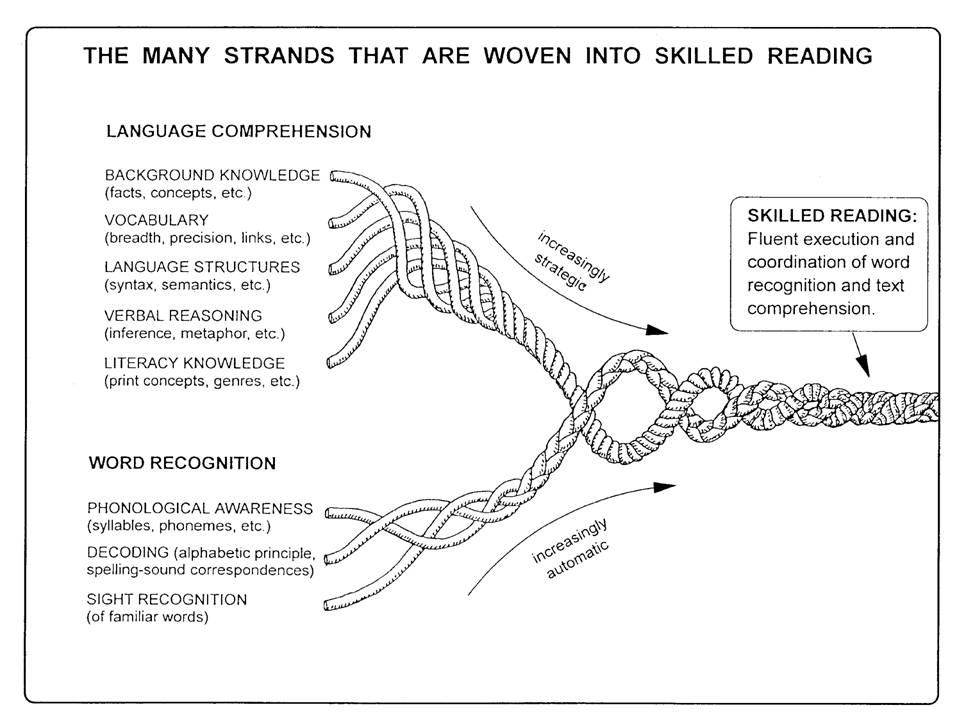

Scarborough’s Reading Rope

Scarborough’s Reading Rope is a visual model that shows how a student’s decoding skills and their reading comprehension skills are inter-connected. As the name suggests, the visual takes the form of a rope as it’s being formed.

To the left is the start of the rope. The strands that represent foundational language comprehension and word recognition skills are distinctly separated from one another to represent the individual foundational reading skills that are woven together in the early years of literacy instruction to form the basis of strong reading skills.

To the right, Scarborough’s illustration shows those strands woven together to create a taut rope, representing a learner who has mastered all of the various skills necessary to succeed as a reader.

This visualization helps explain why it’s so important for students to learn each foundational reading skill as the rope only comes together when each individual strand — or skill — is in place. Otherwise the rope would be frayed!

This well-known visual was created by psychologist Dr. Hollis Scarborough, a senior scientist at Haskins Laboratories in New Haven, Connecticut who has authored a host of research papers on how we learn to read.

Segmentation

Segmentation or segmenting is a decoding strategy that involves identifying the different sounds or phonemes in a word, breaking that word down into its individual parts.

For example, the word “cat” can be segmented by its individual phonemes into /k/ /æ/ /t/.

Sight Recognition

If a student can recognize a word within a fourth of a second, they have what’s known as sight recognition. This is the ability to know a word by sight without having to break it apart to read it.

Closely tied with a student’s orthographic mapping skills, sight recognition allows students to read — and comprehend — more quickly.

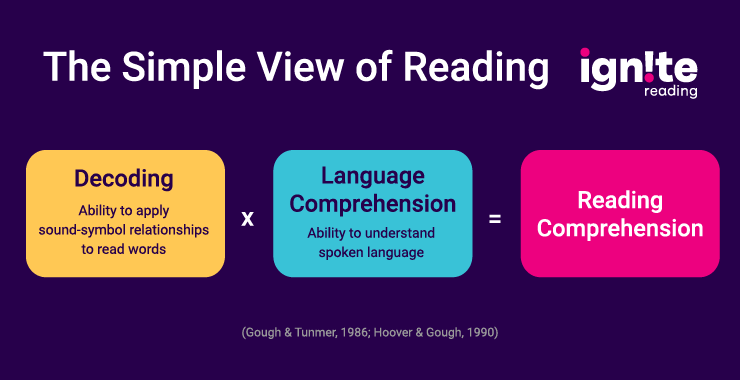

Simple View of Reading

The Simple View of Reading (SVR) is a formula created by cognitive scientists Philip B. Gough and William Tunmer in the 1980s to illustrate the two basic and dependent components of reading comprehension — decoding and language comprehension.

The SVR formula is often presented in the following format: Decoding (D) x Language Comprehension (LC) = Reading Comprehension (RC).

Students need to master the skills represented by D and those represented by LC in order to be able to master reading comprehension.

Using Gough and Tunmer’s simple formula, mastery of one skill set is represented by the number 1. If a child has yet to master any skill in the formula, that skill is then represented by the number 0.

When you substitute numbers for these important reading skills, it’s easy to visualize how intertwined they all are.

If decoding is represented by 0, even if language comprehension is represented by 1, the multiplication rules tell us that the result will be 0. The same goes for the reverse — if language comprehension is represented by 0, it will automatically 0 out mastery of decoding.

Just look at how this would be set up in a math problem:

1 x 0 = 0

0 x 1 = 0

In other words, if one skill or the other has yet to be mastered then reading comprehension can never be achieved.

If a student has mastered both decoding and language comprehension, on the other hand, then the formula becomes 1 x 1 = 1, representing the two skill sets coming together to allow a reader to comprehend text.

Specific Word Reading Difficulties (SWRD)

Specific Word Reading Difficulties, or SWRD, is a reading disability that involves difficulty with a number of foundational reading skills. Students with SWRD typically have average or even higher than average oral language comprehension skills, but they find reading written text to be challenging.

SWRD challenges include difficulty with phonemic awareness and word decoding, as well as inaccurate or non-automatic word reading.

Students with SWRD are typically labeled as having dyslexia.

Structured Literacy

Structured literacy is an approach to reading instruction that puts emphasis on highly explicit and systematic instruction of all important components of literacy, including foundational skills and high level literacy skills.

Although the International Dyslexia Association coined the term, structured literacy instruction is not specific to teaching students with dyslexia.

For decades, most American students were taught to read using a balanced literacy approach — rather than a structured literacy one but extensive research into reading instruction — often called the Science of Reading — has since proven that using an explicit and systematic approach to teach reading is beneficial to all students.

Structure for MLLs

Adopting a structured literacy approach to reading instruction is a critical step for districts and schools looking to improve reading outcomes. Could it also be your district’s key to providing equitable opportunities for multilingual learners to help them acquire English oral and reading skills?

Syllables

A syllable is a unit of pronunciation that contains one vowel sound. A syllable may include surrounding consonants, but it also may not. Each word in the English language is made up of a varying number of syllables.

Early readers begin learning one-syllable words — such as cat or dog — before moving on to multisyllabic words which require them to use more advanced decoding skills.

Trigraphs

Trigraphs are another letter pattern that students learn early on as they build their foundation for reading success. As the prefix tri- implies, these are groups of three letters that work together to represent one sound.

For example, the trigraph -tch can be found at the end of words like “patch” or “hitch.” In this case, the trigraph produces the same sound as the consonant digraph CH — the /ʧ/ sound.

Vowel Teams

Sometimes called vowel digraphs or even vowel trigraphs, vowel teams are units made up of two vowels that work together in a word to produce one sound. For example, the “ai” in rain is a vowel team.

Vowel teams represent common spelling patterns in English, and learning the various teams helps students with both decoding and encoding words.

Word Families

Word families are groups of words in the English language that share the same sequence of letters that produce the same sound.

For example, the words cat, bat, mat, and sat all belong to the same word family — the -at family.

Other examples of word families include:

- -et — get, met, pet, yet

- -ap — map, cap, rap, sap

- -ig — pig, dig, big, wig

Learning to identify word families is part of the foundational skill of learning letter patterns, and it can help early readers read new words more efficiently.

Words Correct Per Minute (WCPM)

WCPM is a measure of reading fluency. Students are timed while reading a passage aloud to determine how many words they are able to read correctly in a 60-second period.

The assessment was developed by researchers Jan Hasbrouck and Gerald Tindal, who based it on years of studying oral reading fluency. The researchers used decades of data to create the Hasbrouck-Tindal Table Of Oral Reading Fluency Norms, a table showing expected oral reading fluency rates of students in grades 1 through 6.

This table can be used as a benchmark to assess whether your students’ reading is on benchmark or on track for their grade level.