You may not remember your brain orthographic mapping the letters and sounds you’re reading right now, but this foundational literacy skill is what makes it easy to read and easy to understand the words in front of you.

Coined in the 1990s by former University of California researcher and psychologist Dr. Linnea Ehri, the term “orthographic mapping” refers to a neurological process that plays a key role in the reading acquisition process. Without it, experts say students cannot develop the reading fluency and comprehension skills they need to engage with the world around them.

What is orthographic mapping, and how does it form an essential bridge between phonics instruction and reading comprehension?

This guide from the Ignite Reading literacy team covers everything educators need to know about this mental mapping process and its role in reading acquisition.

What Is Orthography?

Before we dive into orthographic mapping and reading comprehension, take a look at the definition of orthography itself.

Derived from the Greek words orthos (meaning “right or true”) and graphein (meaning “to write”), orthography is defined by Merriam Webster as either “the art of writing words with the proper letters according to standard usage” or “the representation of the sounds of a language by written or printed symbols.”

In reading science, the word orthography often comes up when discussion turns to instruction related to the skills and concepts of the alphabetic principle — the skills kids need to develop to read increasingly complex text and understand it.

What Is Orthographic Mapping?

If orthography is about writing and sounds, it follows that orthographic mapping would take things one step further.

In simplest terms, orthographic mapping is the process of creating a mental storage system for the letters and words of the English language, along with their associated sounds and meaning.

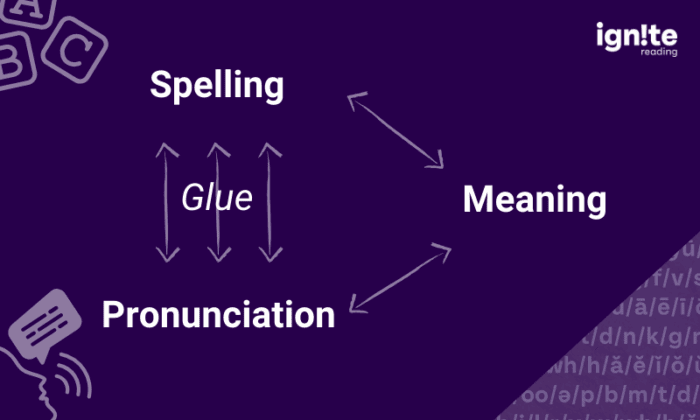

This includes remembering the visual representation of letters and words — quite literally the shapes of the individual letter or combination of letters — and applying knowledge of sounds, meaning, and spelling to that memory, bonding all the pieces together.

This mental “map” is what enables a reader’s brain to quickly process entire words on sight, allowing them to read text quickly and opening the doors to comprehension (more on that soon!).

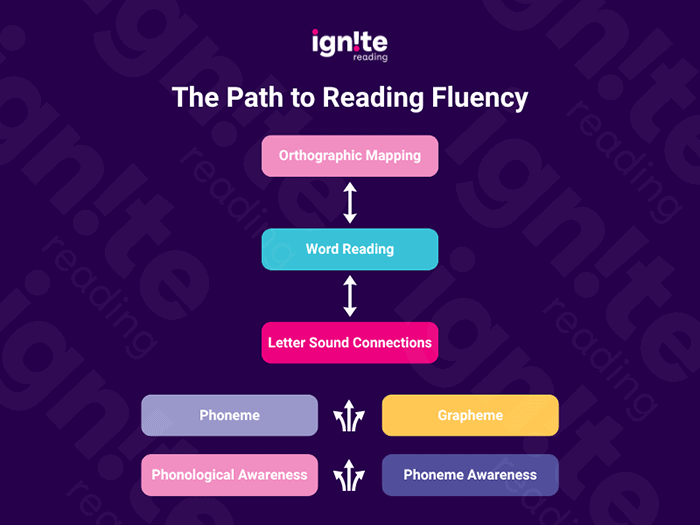

The key to the whole process is phonemic awareness — the ability to segment individual sounds in spoken words — which Ehri calls the “glue” that holds orthographic mapping together.

How Orthographic Mapping Works

How do we ensure kids create these crucial mental maps?

For orthographic mapping to happen, students need to receive explicit instruction in the alphabetic principle. The instruction needs to be delivered in a systematic way with opportunities to learn skills and apply their knowledge to store knowledge in their memory.

The more students have the opportunity to practice blending sounds, decoding words, spelling words, and reading fluently, the quicker they are able to transition these same skill-aligned words from their working memory to their long term memory. This is huge for a student’s reading development!

Once a letter or whole word is stored away in that memory bank, it becomes instantaneously accessible each time a child encounters that letter or word in text. They won’t need to spend time trying to decode each letter or blend sounds together. They now know the word just as well as they know their own name.

What does this look like in action?

Let’s look at a few orthographic mapping examples that help students store words in their long-term memory, so they can easily be retrieved, read, and understood with automaticity (the ability to instantly read a word without having to decode it).

Orthographic Mapping Examples

Orthographically Mapping Blends

The English language is full of intricate letter and sound combinations that early readers need to learn and map to their memory banks.

Among the most common are consonant letter combinations known as blends. When two or more consonants are grouped together to form a blend, the sounds of each are “blended” together.

Unlike digraphs — another sort of letter combination that forms one new sound, like the /sh/ in shoe — the sounds of each letter in a blend are still distinctly heard when a word is said out loud. When the brain has mapped the unique properties of this letter pattern, the reader doesn’t have to think through the blending process.

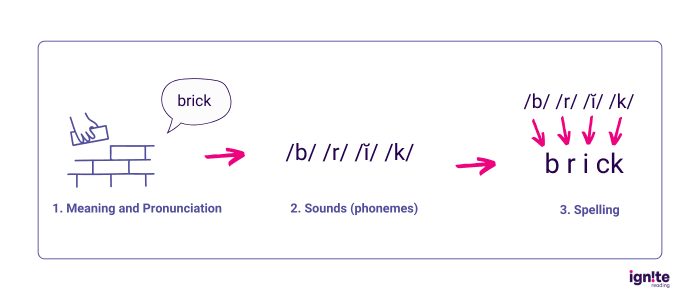

Here’s what it looks like when a child orthographically maps the /br/ blend:

- A student receives explicit instruction on what occurs when the letters /b/ and /r/ appear side by side, learning that they form the /br/ blend.

- The student encounters the /br/ blend several times through blending, decoding, spelling, and connected fluency practice, helping the brain make a solid connection between the phoneme (sound) of the /br/ blend and the grapheme (its written form).

- That connection is orthographically mapped or stored away in the brain or long term memory.

- The student encounters the word “brick” while reading. Their brain automatically pulls the information about the /br/ blend that’s been mapped in the brain, making it easy for the student to immediately recognize the grapheme.

- The student either reads the whole word – if they’ve also learned the consonant digraph /ck/ — or quickly applies their phonemic awareness and phonics skills to blend /br/+ /i/ +/ck/ = “brick.”

- The final part of orthographic mapping is realized when the student knows what a “brick” is and can effortlessly comprehend the word as they fluently read text.

Orthographically Mapping Silent Letters

Silent letters like the /w/ in “answer” and the /c/ in “scissors” present a unique challenge for early readers, as they aren’t pronounced when spoken aloud. Orthographically mapping those letters or letter formations that don’t correspond to a sound in the word’s pronunciation ensures they won’t create confusion while reading text.

When it’s mapped, readers understand that while the letter is silent, it’s still an essential part of the word’s spelling.

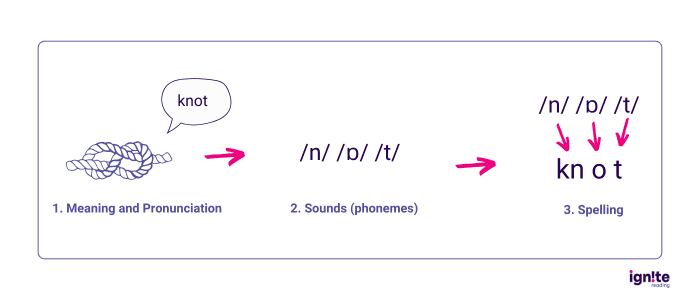

For example, without explicit instruction on the alphabetic principle students encounter words like “knee,” “knife,” or “knock,” their brains must somehow know how to map the visual pattern “kn” to the single /n/ sound.

With explicit instruction, this skill is effectively taught and thoroughly practiced. This allows the /kn/ pattern to be successfully mapped in the brain, and students are able to automatically recognize this silent letter combination and apply the correct pronunciation when encountering new words like “knot” or “knight.” Students can read these /kn/ words and make connections to their meaning.

Reading With Automaticity

According to Ehri’s research, orthographic mapping is a process that continues as students’ develop early reading skills. Ehri defined the reading development process — which forms the foundation for reading comprehension — according to four distinct phases on the alphabetic principle:

Phase 1: Pre-Alphabetic

The reader has not yet mastered letter-sound correspondence, which means they do not make connections between written letters and spoken sounds. This includes three key components of alphabetic knowledge:

- Letter identification

- Corresponding sounds

- Letter formation

Phase 2: Partial Alphabetic

The reader is in the early stages of developing phonological awareness skills and has developed some understanding of letter-sound correspondence. This is evident in their ability to read simple Consonant-Vowel-Consonant (CVC) words like met, hat, and pit.

Phase 3: Full Alphabetic

The reader has developed basic phonemic awareness and is able to associate graphemes with their corresponding phonemes.

At this phase of reading development, a reader still has to decode each individual letter of a word:

- First recognizing each individual letter

- Then using their memory of the associated phonemes

- Finally blending all of the sounds together to form a word.

A student at this stage, for example, has the ability to read Consonant-Vowel-Consonant-e or CVCe words like lake, hike, and cute.

At this point, however, reading is still a laborious process that takes substantial time and taxes a reader’s short term memory. Repeated practice of these decoding skills is what sets students up for phase four.

Orthographic mapping IS NOT memorizing entire words.

In this way, the full alphabetic phase is a lot like developing breath control when you’re learning how to swim. At first you’re able to hold your breath underwater for short periods of time, but it requires you to work hard, gulping in a lot of air before diving beneath the surface and plenty of practice slowly exhaling through your nose while submerged.

All this work helps the body eventually master a rhythmic breathing pattern that coordinates with your stroke movements.

Phase 4: Consolidated Alphabetic

In Ehri’s final phase of reading development, the reader is able to orthographically map the connection between a spoken letter combination or word, how it is spelled, and what it means. They have stored all of this information away in the brain’s memory bank, and it’s ready to be automatically retrieved when they encounter the letter combination or word in print.

When a student reaches the consolidated alphabetic phase, you can expect them to be able to have mastered how to read irregularly spelled sounds and syllabication with a combination of skills and concepts like in locate, plankton, and enchantment.

Once a reader reaches this phase, they have developed what is known as automaticity. They’re able to skip the painstaking process of decoding because the brain automatically visits the memory bank where they find a sort of “dictionary entry” that includes the English alphabetic code they see on the page, plus its meanings, and the sound of the English word they know in spoken language.

Thanks to orthographic mapping, students acquire proficiency along their way on the reading developmental journey and this is happening in a split second, making the process feel effortless, one skill and concept at a time.

| Reading Development Phase | What Happens |

|---|---|

| Pre-Alphabetic | Students rely on visual cues (e.g., word shape, context) to recognize words. They have not yet developed letter-sound knowledge. |

| Partial Alphabetic | Students begin to use some letter-sound knowledge. Word recognition is still partly based on visual cues of letters. |

| Full Alphabetic | Students have a strong understanding of letter-sound relationships. They can decode unfamiliar words by analyzing grapheme-phoneme connections. |

| Consolidated Alphabetic | Students use multi-letter units (e.g., syllables and morphemes) to recognize words, making reading more fluent and efficient. |

Dr. Stanislas Dehaene, a French cognitive neuroscientist known for using functional magnetic resonance imaging to study the brain’s response to both written and spoken language, refers to the memory bank built in orthographic mapping as the “letterbox region” of the brain.

Although much about the process by which this happens is still largely a mystery, Dehaene’s work has determined the brain processes the visual information in this “letterbox region.” He described what happens in his book, Reading in the Brain:

This package of visual information is then shuttled on one of two main routes: one that converts it into sound, the other into meaning. Both routes operate simultaneously and in parallel – one or the other gets the upper hand, depending on the word’s regularity.

Dr. Stanislas Dehaene

Unlocking Reading Comprehension

While reading with automaticity is a key step in reading development, there’s still important work to be done.

Now it’s time for the reader to turn their attention to the meaning of the text.

Reading comprehension is often called the “reason” for reading because it allows the reader to connect to the text, processing the words both alone and together to derive deeper understanding.

Eventually, it becomes second nature, but at the start, little readers and their working memories are going to do a lot of hard work with reading the words themselves. Their brains’ are being taxed in much the same way that they were when they were learning to decode.

The brain must simultaneously manage several complex tasks, seamlessly coordinating:

- Vocabulary access

- Background knowledge activation

- Inference-making

- Comprehension monitoring

Imagine first having to sound out each individual letter or letter combination in the word, then tackling each of these interconnected mental processes, just to read this one sentence. Now imagine having to do all of that to read this entire article. It would take you hours!

This, experts tell us, is why orthographic mapping is crucial for students to become successful at reading comprehension.

Because the brain is automatically doing all the work of matching the written word to the pronunciation and the proper spelling, the reader’s short term memory has been freed up to pick up the new tasks at hand. Readers can dive right into developing their metacognitive strategies in much the same way that a swimmer who has mastered breath control can now concentrate on developing body and arm movements to propel themselves more swiftly across the pool.

The more words that are orthographically “mapped” in the brain, the easier it is to process each word in a text, leaving the brain plenty of room to focus on understanding what is being read.

How to Teach Orthographic Mapping

To help your students make their orthographic maps, implement early literacy instruction that provides:

- Explicit and systematic scope and sequence of skills and concepts with simple to complex skill progression

- Explicit instruction on the alphabetic principle with opportunities for interconnected practice and word analysis

- Introduction of skill and concept

- Blending

- Decoding

- Encoding (spelling)

- Fluency

- Comprehension

- Key instructional practices linked to developmental appropriateness

- Targeted instruction with suite of assessments and data analysis for placement, progress monitoring, and measuring impact

- Corrective feedback with targeted interventions to meet the needs of all learners

Expand Your Early Literacy Understanding

- Foundational Reading Skills Primer: What They Are + Key Vocabulary Explained — Go beyond orthographic mapping with an A to Z guide to the skills that make up the foundation of reading.

- How to Build a Literacy Ecosystem for Your School That Really Works — Explore actionable tips for building a Science of Reading-aligned literacy framework in your district or school to drive student achievement.