There are few skills as fundamental to students’ future success in school and life as learning to read, and yet we are facing a literacy crisis in America — one that educators are scrambling to address.

Is learning to read really that hard? And if it is, what can we do about it?

Literacy Today

Adult literacy levels in the U.S. fall far behind those of other industrialized countries, and an estimated two-thirds of American kids cannot read fluently.

The numbers have not gone unnoticed. Legislators in more than 45 states have passed laws in recent years to reboot literacy education methods, and district and school leaders across the nation are embarking on a journey to rebuild their literacy ecosystems from the ground up.

Neuroscientists and cognitive psychologists alike say the science shows nearly all kids can be taught how to read fluently and make meaning of connected text.

So, how do we make learning to read a standard part of the American education system and guarantee all kids learn the foundational skills they need before they start 2nd grade?

We need to start by addressing the simple fact that learning to read is not a natural process for the human brain and that the road to fluency looks very different for some students than it does for others.

Let’s explore why learning to read can be so darn hard for so many kids … and what we can do to give kids exactly what they need to become fluent readers.

Why Is Learning to Read So Hard?

Linguists believe homo sapiens have communicated with one another through speech for as much as 200,000 years.

Perhaps it’s no surprise then that most toddlers will pick up new words with no direct instruction and little to no repetition, even learning multiple languages just from hearing them spoken in and around the home.

Written language, on the other hand, was invented less than 5,500 years ago. It was an important advancement that would pave the way for the creation of governments and more complex economic systems, but it would also require the human brain to take on an entirely new task — learning to read what was written.

Put in that context, reading is a relatively new skill for the human species, and neuroscientists have posited that means evolution hasn’t had a chance to catch up with this “new” means of communication. That means the human brain is still dependent on neural circuitry that evolved to process spoken — rather than written — language.

Is it a surprise, then, that the same toddler who so easily learned to speak in complete sentences — seemingly through osmosis — would require not just modeling but also repeated reading practice to attain proficiency in reading?

When you layer on the specific foundational skills students need to develop to become fluent readers — like phonics — it becomes easier to understand just why learning to read is so challenging.

Cracking the Code

Do you remember encountering code-cracking challenges in puzzle books as a kid? These puzzles were like a secret code with sequences of numbers, pictures, and letters. You would match each number and picture to a corresponding letter to decode the message.

English is that same level of unknown code for a brand-new reader, and learning to read requires them to develop the ability to decode.

Consider what this process looks like for a small child.

We present a set of squiggly lines — which we call the alphabet — and tell pre-readers that these squiggly lines all mean something important.

What’s more, we present our early readers with these same squiggly lines and shapes in different fonts and different colors, and yet we insist that these very different looking images represent the very same thing — the differences do not matter.

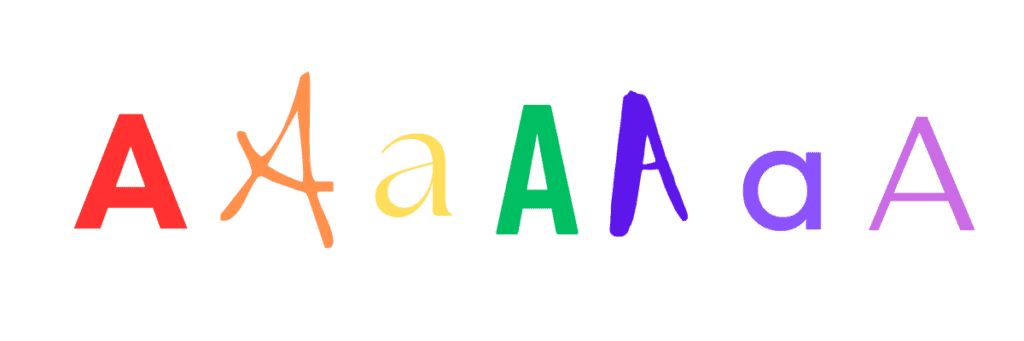

Consider the letter A, written below in seven different fonts and seven different colors. Try to imagine viewing each one for the very first time.

Would you easily identify them all as the same letter?

A is, of course, just one of 26 letters of the alphabet — all of which have upper and lowercase versions that look completely different from one another — that our early readers have to contend with. We ask kids not merely to match the letter name to the visual but to develop a host of other skills that build off that letter recognition.

Working With Phonemes

In order to read fluently, kids must also master letter-sound correspondence. That means they must be able to match each letter shape to a phoneme — the smallest unit of sound that carries meaning.

For example, kids need to understand that the “s” in “sock” makes the /s/ sound, or the “b” in boy makes the /b/ sound.

But wait … there’s another trick afoot!

There are 26 letters in the English alphabet, but the English language contains more than 26 phonemes.

To make matters increasingly confusing, a single phoneme can show up in a variety of ways.

Listen to the phoneme /f/ in the audio clip below.

In the word “foot,” the phoneme is represented by the letter f. But in the second word, “graph,” that same phoneme is represented by the digraph “ph” because — of course — two letters can come together to form a whole new sound. In fact, three letters can also work together to form just one sound — like the “dge” in “edge.”

Oral Segmentation

Learning to read fluently also requires our students to grapple with increasingly complicated parts of the code as they master each foundational skill, so we don’t stop at teaching kids to match individual letters to the sounds (or phonemes) they produce.

In order to build phonological awareness — the ability to recognize the sound structure of different words and sentences — students next need to master oral segmentation, the process of breaking a whole word down into its individual phonemes.

Let’s say a student encounters the word “big.” To orally segment, they will need to break it down into the three individual sounds associated with the letters b, i, and g — /b/ /ɪ/ /ɡ/ — slowly saying each sound out loud.

Blending

Also crucial to developing phonological awareness and word recognition is for students to master blending — which means putting those individual sounds back together to form a word, with /b/ /ɪ/ /ɡ/ becoming “big” or /r/ /ɛ/ /d/ becoming red.

Onset and Rime

After blending, students will tackle the various letter patterns that make up the English language, learning how clusters of letters that often appear together work.

That includes learning to blend words that contain consonant clusters (called onset) with a vowel and a final consonant (called a rime) to form a complete word. This unlocks part of the code. Now kids can see how individual letters work together to make sounds.

Let’s look at the monosyllabic (single-syllable) word “mat.”

Students who have mastered letter-sound correspondence should be able to identify the three individual sounds (or phonemes) represented by the letters m, a, and t. As they move into letter patterns, they learn to break mat down to:

- m — the onset of the word

- at — the rime of the word

The rime -at is, of course, repeated in countless English words like “cat,” “bat,” “rat” and so on. This means students who are able to identify the rime in simple words like this can apply that knowledge to more quickly decode a host of -at words, which helps not just with reading but with spelling too.

Vowel Teams

English has long been considered one of the most difficult languages for non-native speakers to learn, and it’s in part due to the complex letter pattern rules that children learn in the primary grades.

To drive this point home, look at the vowel pairs below. They all appear entirely different, and yet in English they all make the same sound:

- ai in rain

- ea in great

- ei in vein

- ay in play

Despite the tremendous complexity of the English language, if students learn all of the skills above and develop a solid foundation and understanding, they become strong decoders who can apply those skills and rules to more and more sophisticated words.

In other words, they become strong readers.

How the Brain Learns to Read

Building a good foundation is critical for students’ future success, and to get it right, we turn to science to understand what it is kids need most to become fluent readers.

Consider what studies of the brain have taught us about letter-sound correspondence instruction.

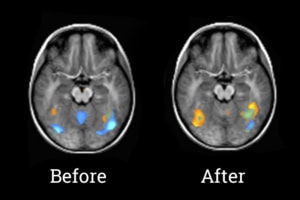

When Swiss and Finnish neuroscientists used functional MRI scans to look at kindergartners’ brains, they were able to see a distinct difference in how the students’ brains responded to printed text before and after learning letter-sound correspondence.

Before the instruction, when kids were exposed to text, the language centers in their brains remained dark, as you can see in the left side of the brain on the “before” image below. Without those phonetic foundations, the brain was essentially stumped.

As you see in the “after” image, however, when the students were taught to make these connections, those same centers on the left of the brain literally lit up (seen in bright yellow) with understanding.

What scans like these tell us as educators is that understanding how the brain learns to read is key to cracking our own code — the code to designing reading instruction models that serve all students.

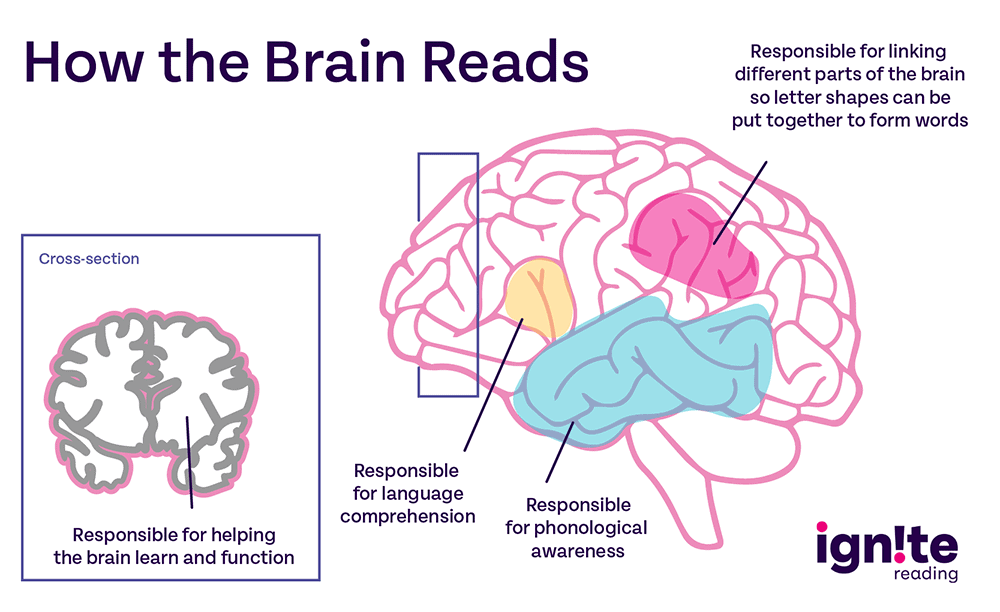

Studies of the brain also tell us that there are four specific parts of the brain required to work in order to read:

- The Broca’s area of the frontal lobe — Responsible for language comprehension

- The temporal lobe — Responsible for phonological awareness

- The angular and supramarginal gyrus — Responsible for linking different parts of the brain so letter shapes can be put together to form words

- White matter — Responsible for helping the brain learn and function

Studies have told us that the brain’s white matter sets kids who easily learn to read apart from their peers.

According to a 2012 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Stanford University researchers say strong early readers have strong signals in two of the brain’s white matter tracts:

- The arcuate nucleus — Connects the brain’s language centers

- The interior longitudinal fasciculus — Links the brain’s language centers with parts of the brain that process visual information

Of particular interest was what the Stanford researchers saw when they looked at the brains of kids who have a harder time reading. Those learners had the exact opposite pattern in their white matter tracts.

When they looked at the white matter again after the students received reading skills intervention, the tracts had changed to look more like those of their peers.

This tells us that kids who are not strong early readers can become fluent readers — it just takes specific instruction in foundational reading skills.

Nancy Young’s Ladder of Reading & Writing

Of course, we can’t see inside the heads of our learners and evaluate their white matter — or any other part of the brain — but we do know there’s a spectrum of learning needs identified by scientists who have studied how we learn to read.

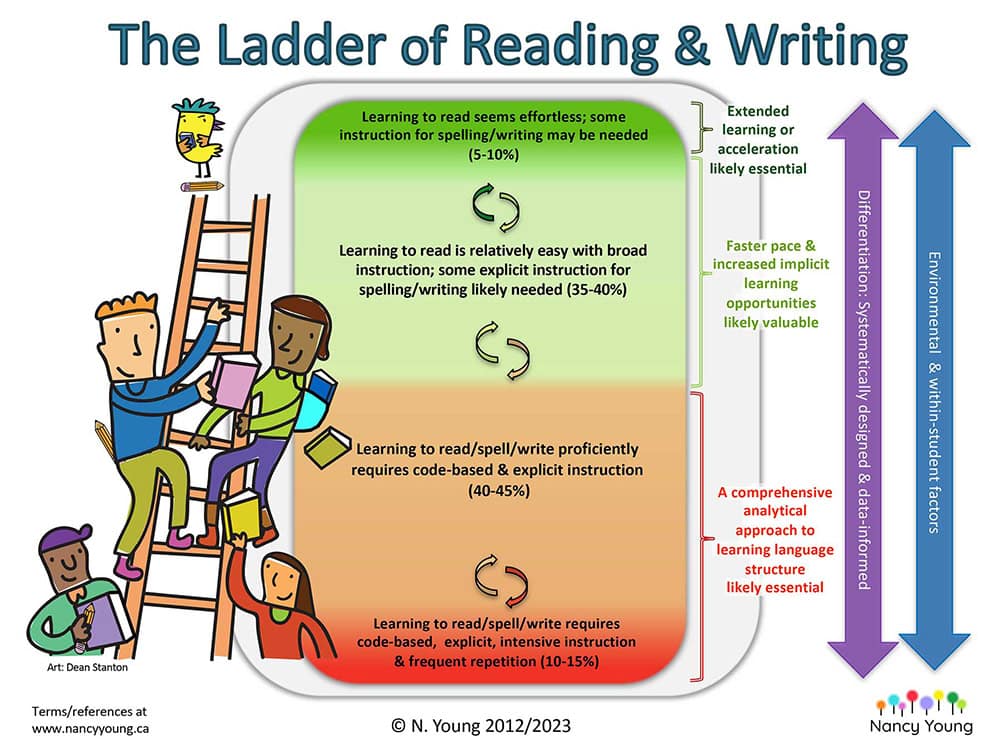

Those studies tell us that reading comes easy to just 5 to 10 percent of kids. For these kids, learning to read is an effortless process, one that comes as naturally as throwing a football might be to a natural athlete. The majority of kids, however — as much as 60 percent — require explicit instruction to master foundational reading skills.

Canadian educator Dr. Nancy Young created a visual representation of this spectrum, detailing four distinct types of learners, known as Nancy Young’s Ladder of Reading and Writing.

Here’s how Young breaks down each group:

- 5-10 percent of students — Learning to read seems effortless; some instruction for spelling/writing may be needed

- 35-40 percent of students — Learning to read is relatively easy with broad instruction; some explicit instruction for spelling/writing likely needed

- 40-45 percent of students — Learning to read/spell/write proficiently requires code-based and explicit instruction

- 10 to 15 percent of students — Learning to read/spell/write proficiently requires code-based, explicit, intensive instruction and frequent representation

All kids need varied amounts of direct instruction and practice in order to develop automaticity and fluency and reading, and Young’s ladder helps explain why those amounts can vary so widely from student to student.

Aligning Reading Instruction With What The Brain Needs

Young’s reading ladder doesn’t just confirm that learning to read looks different for different kids and the journey up the Ladder may be more difficult for some.

It tells us that general classroom instruction is not enough for most early readers, and this is not due to any failings on the part of classroom teachers.

When you have a room of 30 kids and you’re one teacher trying to meet that need across the board, differentiating instruction for every single student is impossible.

And yet, if we want all students to be able to decode automatically, we have to acknowledge that the majority of students need to be taught the code explicitly, intensively, and with frequent repetition in order to get to the point of automaticity. It’s simply what their brains need.

Here’s how we recommend districts and schools make that happen.

- Ensure that all classroom reading instruction is in alignment with the learning needs of the students receiving that instruction (content, methods, and materials).

- Use evidence-based assessment tools to ensure we supply students with extra support when they need it and how they need it.

- Create a Tier 1 framework that is based on differentiated grouping (this could be within a classroom, across a grade or between grades), recognizing that some students in the red area of Nancy Young’s Ladder of Reading and Writing may require Tier 2 and Tier 3 supports — such as 1:1 literacy tutoring.

Yes, learning to read is hard. But with a solid framework for literacy instruction that’s been built on evidence-based methods, nearly all kids can become confident, fluent readers.

About Ignite Reading

Ignite Reading delivers 1:1 online tutoring to students who need extra support in learning to read. Our expert tutors teach students the foundational skills they need to become confident, fluent readers by the end of 1st grade.

With a team of literacy specialists and highly trained tutors, we provide daily, targeted instruction that quickly closes decoding gaps, so students can successfully make the transition from learning to read to reading to learn.