Enter any conversation about kids and literacy instruction these days, and the words “Science of Reading” are almost guaranteed to come up.

A term used to sum up decades of reading research, the Science of Reading (or SOR for short) has been hotly debated in state legislatures nationwide, skyrocketed a certain education podcast to the top of the charts, and is dominating discourse in districts across the country in recent years.

But what is the Science of Reading, exactly, and where did it come from? For that matter, just how effective is reading instruction that’s aligned to the Science of Reading?

To help you get up to speed quickly, we’ve dug deep into the history books to track the origins of SOR, and we’ll explore the prominent research that led up to its wide-spread use today.

What Is the Science of Reading? A Simple Definition

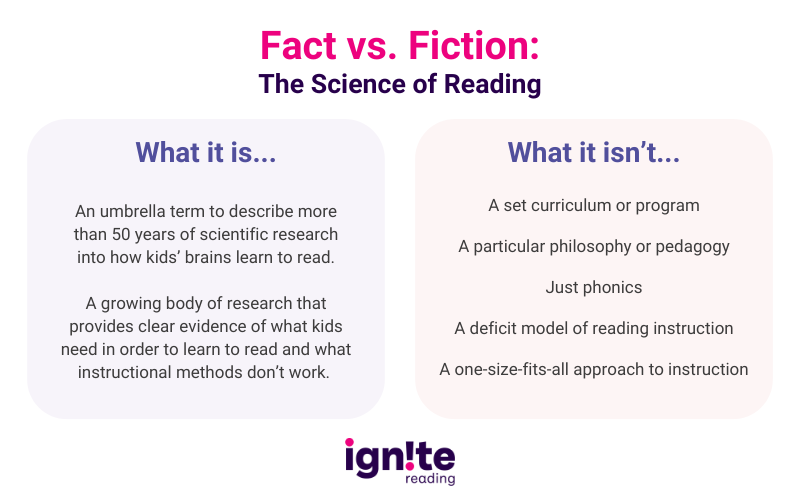

The Science of Reading is an umbrella term that describes a wide-ranging body of scientific research into how kids’ brains learn to read and the challenges learners encounter along the way.

Stretching back more than 50 years, the research that falls under this umbrella includes findings from developmental and educational psychologists and cognitive scientists and neuroscientists, which provides converging evidence of what kids need in order to learn to read fluently.

With so much research, there are enough findings to provide a clear understanding of which instructional methods are ineffective and what really works. This gives us a basis for building curricula and programs that truly align to what students need as they learn to read.

SOR doesn’t refer to any single aspect of teaching reading or any specific program or curriculum for reading instruction. And, despite a pervasive myth, it’s also not simply focused on phonics.

Where Did the Science of Reading Come From?

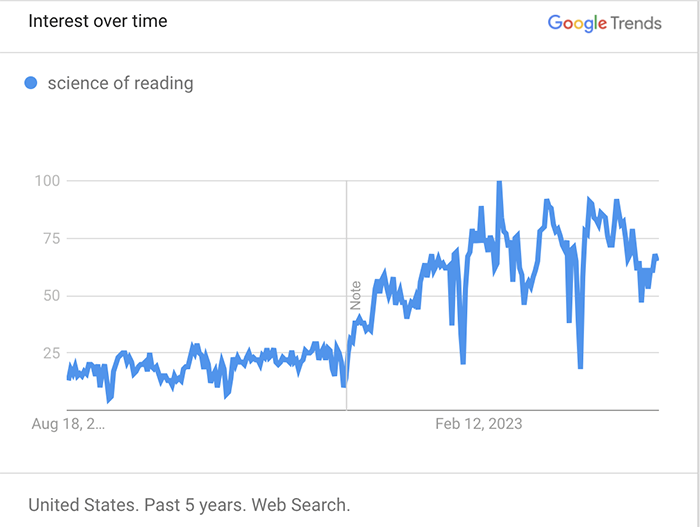

Does it feel like SOR took over the educational zeitgeist suddenly and almost out of nowhere? Google Search data backs up the feeling. The search engine shows Internet queries for the term began to take off in April 2022, and they’ve been on the rise ever since.

But the history of “Science of Reading” dates back much, much farther … nearly 200 years.

Well before neuroscientists could start scanning kids’ brains with MRI machines to understand what happened as they learned to read, at least one educator was calling on colleagues to turn to the science — or his version of it anyway.

One of the earliest pedagogical uses of “Science of Reading” has been traced back to at least the 1830s when it was first mentioned in the journal American Annals of Education and Instruction, for the Year 1836, Vol. 6. The phrase appeared in a letter to the editor decrying a lack of systematic spelling instruction in schools of the era.

Signed only “Experience,” the letter posits that students find reading to be a “difficult and disagreeable task” because adequate time is not spent teaching students to “master every variety of the word, from the most difficult of one syllable to those of many.”

“Spelling may perhaps be considered as the dry rudiments of the beautiful science of reading,” the letter writer notes, later advising, “It is highly necessary to be methodical, exact, decided and firm in all the regulations of your reading classes.”

The “Experience” letter offers little more than the author’s own opinions to support this version of the “Science of Reading,” but it bears at least passing resemblance to the actual findings of modern scientists that fall within the modern Science of Reading.

Just as “Experience” surmised back in the 1830s, scientific researchers have since proven that the majority of students require systematic, explicit instruction in letters and sounds in order to learn to read, and we now have the converging body of research we call “the Science of Reading” to back up the findings.

Important Research in the Science of Reading

How did we go from the phrase “Science of Reading” appearing in a letter to the editor in 1836 to 39+ states adopting Science of Reading legislation or policies today??

That winding path can be tracked through a look at some of the important research exploring how humans learn to read and the most effective instructional methods that have been conducted in the past century.

Orton’s Theory of Dyslexia — 1925

Research Conducted By — Dr. Samuel T. Orton

Dr. Samuel T. Orton was one of the first U.S. researchers to identify dyslexia as a reading difficulty and to advocate phonics instruction for students who’d been diagnosed with dyslexia.

A neuropsychiatrist and pathologist who worked with adults with brain damage at the Iowa State Psychopathic Hospital, Orton set out to explain why children who had not suffered brain injury were displaying symptoms similar to those exhibited by the adults who had sustained language loss. He theorized that children who do not establish hemispheric dominance in particular areas of the brain display specific developmental language disabilities. He presented his theory of “word-blindness” at the 1925 annual meeting of the American Neurological Association in Washington, D.C..

Dr. Orton later joined forces with educator Anna Gillingham to create what’s still known today as the Orton-Gillingham method, an instructional approach that involves explicitly teaching the connections between letters and sounds to help students learn to read.

Why It Matters

Orton wasn’t the first researcher to discover that dyslexia existed — that finding is credited to German neurologist Adolf Kussmaul who coined the term “word blindness” — but he’s largely credited with laying the groundwork for both understanding specific reading disabilities and the need for tailored reading instruction.

We now know that dyslexia is a common learning disability that makes it difficult for readers to decode and spell written words — as much as 20 percent of the American population is believed to have it.

Chall’s Stages of Reading Development — 1967

Research Conducted By — Dr. Jeanne Chall

Jeanne Chall was a psychologist at the Harvard Graduate School of Education who received a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York to synthesize various studies of reading instruction that had been completed between 1910 to 1965.

In the resulting book published in 1967, Learning To Read: The Great Debate, Dr. Chall proposed that reading development occurs in six specific stages, which she broke down across approximate ages:

| Reading Stage | Age Range |

| Pre-reading | Approximately Birth to Age 6 |

| Initial reading or decoding | Approximately Ages 6-7 |

| Confirmation and fluency | Approximately Ages 7-8 |

| Reading for learning the new | Approximately Ages 8-14 |

| Multiple viewpoints | Approximately Ages 15-18 (high school) |

| Construction and reconstruction | Approximately Ages 18+ (college/beyond) |

Chall also concluded that “code emphasis” — her name for phonics — was significantly more effective than the whole language method for teaching kids to read.

Why It Matters

Advocating for a code-emphasis approach, Chall’s work established the importance of a systematic approach to reading instruction and the notion that early reading is significantly different from more mature reading.

The Simple View of Reading — 1986

Research Conducted by — Philip B. Gough and William Tunmer

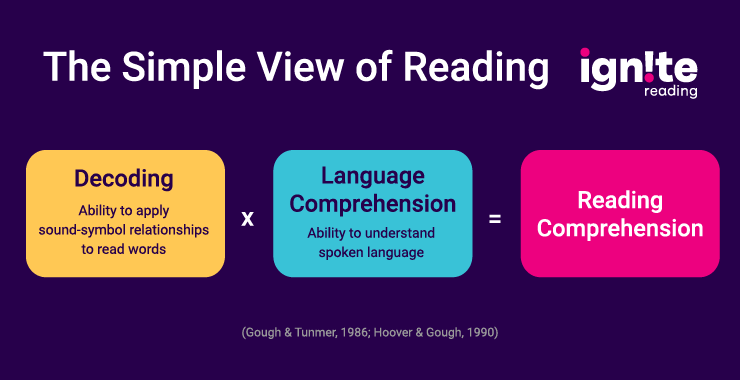

In the late 1980s, cognitive scientists Philip B. Gough and William Tunmer posited that there are three types of reading disability:

- An inability to decode

- An inability to comprehend

- An inability to both decode and comprehend

In order to clarify the role of decoding in reading and reading disability, Gough and Tunmer proposed what they called a “Simple View of Reading.” Set up like a mathematical equation, the view illustrates that reading comprehension is the product of two primary components: decoding (D) and language comprehension (LC), where reading comprehension (RC) is expressed as RC = D x LC.

Why It Matters

The Simple View of Reading helped establish the importance of both decoding and linguistic comprehension for reading comprehension. More than three decades since Gough and Tunmer first presented their theory, it’s still one of the most widely used in education.

The Matthew Effect in Reading — 1986

Research Conducted By — Dr. Keith Stanovich

Around the same time that Gough and Tunmer were developing their Simple View, Canadian psychologist Dr. Keith Stanovich was publishing his theory on the reading proficiency gap that exists between students who learn to read quickly and easily vs. those who have difficulty reading at the start.

Dr. Stanovich described how early success in reading leads kids to read more, which in turn leads to greater skill development. At the same time, he noted that early difficulties in reading lead students to read less, which results in a widening gap in literacy skills over time.

The theory borrows from the Matthew Effect or Matthew Principle, a social phenomenon in which the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. The phenomenon got its name in the 1960s from sociologists Robert K. Merton and Harriet Zuckerman who drew inspiration from the Bible’s Gospel of Matthew.

Why It Matters

The Matthew Effect in reading has helped support the need for early intervention in reading.

National Reading Panel Report — 2000

Analysis Conducted By — National Reading Panel

In the late 1990s, then Director of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Duane Alexander and then Secretary of Education Richard Riley were called on by Congress to convene a panel of experts to analyze research into the various approaches to reading instruction. Fourteen individuals from around the country were chosen, including leading scientists in reading research, representatives from colleges of education, reading teachers, educational administrators, and parents.

That panel’s review of research from peer-reviewed journals covered more than 100,000 different studies.

The National Reading Panel Report, delivered to Congress in 2000, identified five pillars of effective reading instruction that are often referred to as the five components of the Science of Reading:

- Phonemic awareness

- Phonics

- Oral Reading Fluency

- Vocabulary

- Comprehension

Why It Matters

The five pillars outlined in the report have given shape to reading instruction policies and practices throughout the U.S. education system. Studies completed in the years since the report was released have only strengthened the case for building literacy instruction around them.

Scarborough’s Reading Rope — 2001

Research Conducted By — Dr. Hollis Scarborough

Dr. Hollis Scarborough is a psychologist and literacy researcher who has contributed significantly to the Science of Reading, authoring and co-authoring more than 40 research papers that give us a window into the way students best learn to read.

Dr. Scarborough may be best known, however, for her creation of Scarborough’s Reading Rope, a visual representation that illustrates the key skills that must be mastered in order to become a proficient reader.

The Reading Rope consists of two intertwined strands — language comprehension and word recognition — which encompass all of the skills needed to become a skilled reader with strong reading comprehension skills.

In Dr. Scarborough’s visual model, the strands are weaved together into a rope to show the connectedness of the skills and emphasize how proficient reading is dependent upon both strands being developed effectively.

Why It Matters

Dr. Scarborough’s work complements the Simple View of Reading in illustrating how interconnected early reading skills are. Adding in sub-skills, the rope goes one step further to help educators understand how those sub-skills combine to support learning to read.

Science of Reading Legislation and State Policies Today

These studies — and countless others — have helped shape not just educators’ understanding of what students need to become fluent, confident readers but politicians’ too.

Since 2013, the majority of states across the country have either passed laws or enacted policies to support Science of Reading-aligned instruction in schools.

3-Cueing Bans

States have even banned schools from using instructional methods based on disproven theories like 3-cueing, a debunked idea that early readers should be taught to look to three sources of information to help them guess words they encounter while reading.

Three-cueing is banned in each of the following states:

- Arkansas

- Florida

- Georgia

- Indiana

- Louisiana

- Minnesota

- North Carolina

- Oklahoma

- Ohio

- South Carolina

- Texas

- Virginia

- West Virginia

- Wisconsin

More Helpful Science of Reading Resources

Want to dive deeper into the Science of Reading and teaching students to read?

Here are some helpful resources:

- How to Build a Literacy Ecosystem for Your School That Really Works — Explore actionable tips for building a Science of Reading-aligned literacy framework in your district or school to drive student achievement.

- Foundational Reading Skills Primer — Learn more about the five components of the Science of Reading and other foundational reading skills.

- Eyes on Reading: Dr. Stanislas Dehaene with Emily Hanford — Presented by the Planet Word Museum, this conversation between neuroscientist Dr. Stanislas Dehaene and journalist Emily Hanford will take you on a deep dive into the human brain and how it learns to read.

- What Works Clearinghouse — Created by the Institute of Education Science, the WWC includes reviews of the quality and efficacy of existing educational research, practice guides and intervention reports highlighting promising programs, teaching methods, and policies.

- 6 Science of Reading Podcasts Every Educator Should Add to Their Playlist — Listen to the stories behind the science, and get to know more about the history of literacy education in the U.S.

About Ignite Reading

Ignite Reading delivers 1:1 online tutoring to students who need extra support in learning to read. Our expert tutors teach students the foundational skills they need to become confident, fluent readers by the end of 1st grade.

With a team of literacy specialists and highly trained tutors, we provide daily, targeted instruction that quickly closes decoding gaps, so students can successfully make the transition from learning to read to reading to learn.