Adopting a structured literacy approach to reading instruction is a critical step for districts and schools looking to improve reading outcomes. Could it also be your district’s key to providing equitable opportunities for multilingual learners to help them acquire English oral and reading skills?

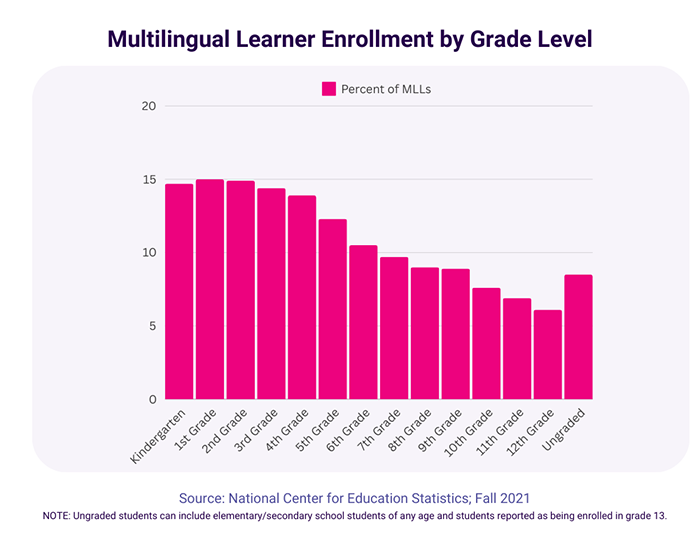

Multilingual learners (MLLs) or English Language Learners (ELLs) now make up almost 11 percent of the K-12 enrollment in the U.S,. and they’re the fastest-growing student demographic. But for decades, these students have lagged well behind their native English speaking peers in reading achievement.

This must — and can — change, and adopting a structured literacy approach is one step in the right direction.

What Is Structured Literacy? Defining the Structure

You may be familiar with the term, but what’s the structure in structured literacy, anyway?

“Structured literacy” first cropped up in educational circles in 2016 when the board of directors at the International Dyslexia Association (IDA) assigned the name to its approach to literacy instruction, which focuses on teaching students the structure of the English language and how we use it to read and write, including the relationships between speech sounds and written text, sentence structure, and meaning.

In the years since the IDA structured literacy definition was first introduced, its popularity has exploded. These days the term serves as an umbrella for an explicit, systematic approach for teaching oral and written language skills to any student — not just those with a dyslexia diagnosis.

The majority of students learn to read best with this kind of explicit and progressive approach, something Canadian educator and literacy education specialist Dr. Nancy Young illustrated in her now famous Ladder of Reading and Writing.

Young’s translational framework shows that as much as 90 percent of learners need at least some explicit instruction in order to become fluent readers and writers, and that includes multilingual learners.

Supporting All Students

There’s even evidence that structured literacy instruction can work regardless of the learner’s primary language. Researchers at the University of Toronto and Canada’s Brock University, for example, discovered no differences in reading intervention outcomes between English language learners and native English speakers. This suggests that systematic and explicit reading intervention works no matter the learner’s home language.

How Multilingual Learners Score in Reading

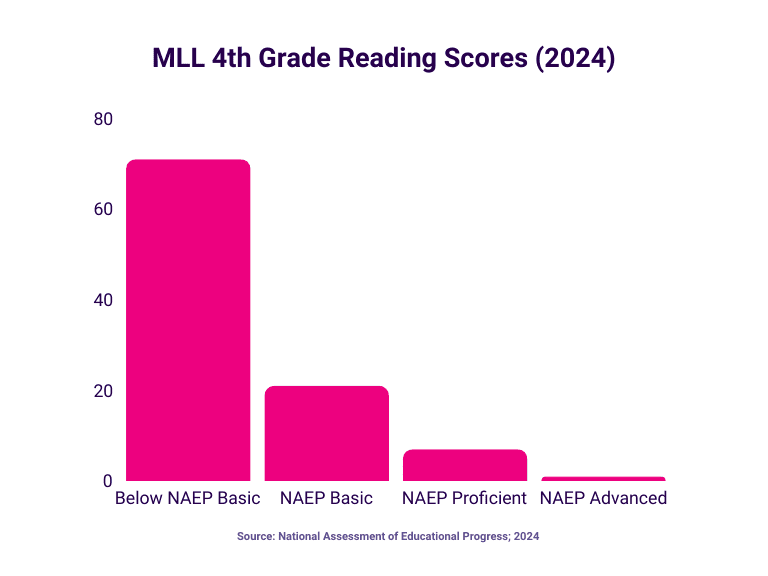

Nationally, just 31 percent of 4th graders tested as proficient readers on the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading test.

Equally troubling is the growing opportunity gap affecting our multilingual students:

- A comparison of NAEP scores from 2022 and 2024 shows average reading scores for 4th graders in the English learner (the official term used on the national test) category decreased a full 5 points.

- On average, multilingual 4th graders scored 34 points lower than their peers on the 2024 national assessment and 53 points below proficiency.

- Just 8 percent of these students scored at proficiency or higher on the 2024 test.

This does not mean that multilingual learners are unable to become proficient readers.

Research tells us 95 percent of people can learn to read with evidence-based assessment and structured literacy instruction, and there’s plenty of evidence that this combination is also effective for kids who are learning English as a second (or third) language.

One study by researchers at The Center for Research and Reform in Education at Johns Hopkins University found that multilingual learners who received structured literacy instruction for one school year via Ignite Reading’s 1:1 tutoring program gained more than 5 additional months of learning compared to national averages.

Not only did these students make consistent progress, but researchers found they did so at the same rate as native English speaking students.

How can you achieve the same results for your multilingual learners? Read on to explore the ways structured literacy can make a difference for your multilingual learners too.

Challenges for Multilingual Learners Learning to Read in English

It’s not easy to learn to read. This is true not just for our MLL learners but for students who have been speaking English their entire lives.

Scientists attribute the challenges most early readers face to the makeup of the human brain and the way it processes text — humans just haven’t evolved enough as a species for reading skill acquisition to be easy.

The intricacy of the English language also makes learning to read it especially hard in comparison to other languages spoken around the globe.

Many of the world’s languages have what’s known as a transparent or shallow orthography. This means that each of the written symbols of the language typically relate to just one or two specific spoken sounds. This is true of Spanish, German, Turkish, and dozens of other languages, but not of English.

English has what linguists call an opaque or deep orthography. Many of the 26 letters of our alphabet produce a variety of sounds, depending on the situation. The English language has 44 different speech sounds (called phonemes), which can be made by hundreds of spelling alternatives.

Just consider the common (but entirely different) sounds made by the English letter g.

- Hard g — When a g is followed by the letters a, o, or u, it usually makes the hard g sound heard at the start of “game” or “gum.”

- Soft g — When a g is followed by the letters i, y, or e, it usually makes the soft g sound. In these instances, it sounds more like the letter j, like the initial sound in the words gym or gel. There are exceptions, however. In words like “girl” and “gift,” the g is hard, despite the presence of the letter i.

- -Ough — When the letter g appears in the grapheme “ough,” its pronunciation is neither that of a hard g or soft g. In fact, there’s not even a consistent pronunciation for “ough” which produces a long u sound in the word “through” but creates a long o sound in words like “dough” and “borough.” There are more than a half a dozen sounds that -ough can make, depending on the word.

For anyone learning to read in English, these inconsistencies can feel a bit like playing a game of soccer where the goal posts keep moving.

For the millions of multilingual learners enrolled in the U.S. public schools, another layer of complexity gets added on — they’re also learning to speak the language.

These students approach learning to read in English with a range of literacy skills and academic needs almost as diverse as the English language learner population itself.

Some English language learners may already be proficient readers in their home language, while others have yet to acquire literacy skills in any language. Some of these children come to school with first-language oral proficiency; others are still developing their oral language skills in the language spoken at home, and so on.

How Structured Literacy Helps Multilingual Learners

Recognizing that multilingual learners are not a monolithic group, and students have varying levels of oral and reading proficiency, explicit, systematic reading instruction still addresses the challenges unique to learning to read English as a second language.

Let’s take a look at some of the most common challenges and how to help multilingual learners with structured literacy instruction.

1. English Speech Sound Acquisition

Have you ever tried to pronounce a word in a foreign language? Did you stumble over the pronunciation?

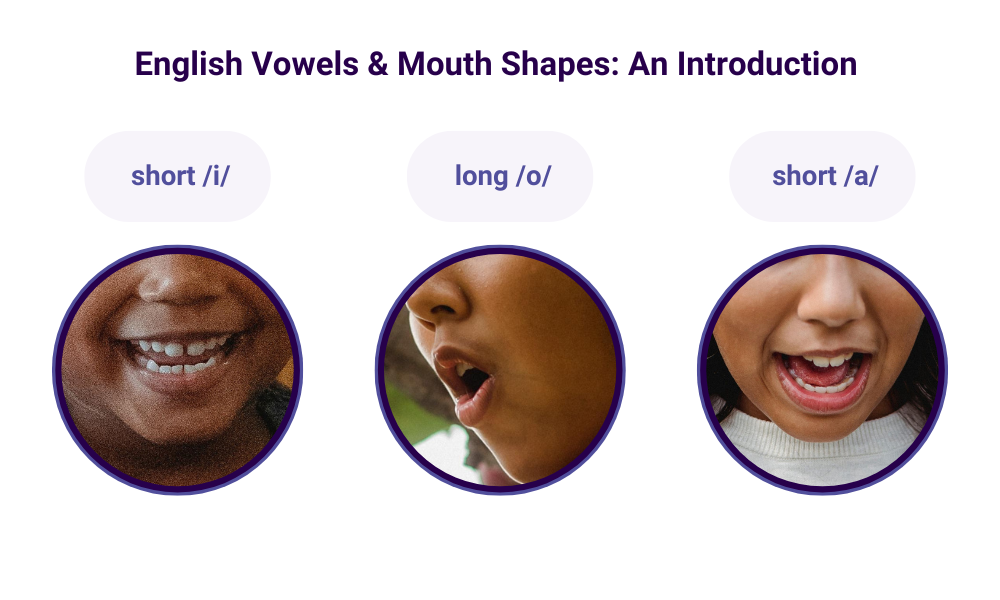

The bones and muscles of our mouths, along with the lips and tongue and even the roof of the mouth, all help us produce the noises singular to a specific language. The way we move our mouths to make those sounds is different depending on the language being spoken.

Not only do multilingual learners face learning new mouth positions to speak their new language, but often the speech sounds specific to the English language are completely unfamiliar. Some of these sounds may not even exist in their native language.

Spanish — one of the languages described earlier as having a shallow orthography — has just five vowel sounds for speakers to learn, while English (with its deep orthography) has four times that!

Spanish speaking students represent about 76 percent of the multilingual learners in the U.S., and they typically have to learn a host of new vowel sounds (and flex new mouth muscles) to build their English proficiency.

Take, for example, the schwa sound. The schwa is what’s known as a relaxed or unstressed vowel sound. It’s the most common vowel sound in English, but relaxed sounds like the schwa don’t exist in Spanish. All Spanish vowel sounds are pronounced distinctly.

The result is a fairly common stumbling block for Spanish speaking students who are still on an oral language acquisition journey.

Pronounced “uh” by native English speakers, the schwa shows up in the word “sofa” as the ending sound — soh-fuh.

For a multilingual learner reading aloud, a word like sofa is more likely to come out as “soh-fah.”

How Structured Literacy Instruction Can Help

Fortunately, structured literacy is well-designed to teach English speech sounds.

A key component of this explicit instruction model is teaching phonemic awareness, which amounts to the ability to understand that a specific speech sound is created by a letter or a group of letters. The model also requires teachers to model tasks using clear, easy instructions that will help their students better understand the steps required for completion.

In other words, even if a student’s native language does not have a particular letter or sound, structured literacy uses a methodology that teaches every sound as if it were new. The instructor will introduce every letter and sound before moving into more complex patterns, scaffolding learning in a way that supports language acquisition for MLLs.

What It Looks Like in Practice

- Teacher modeling provides students with repeated exposure to the sounds.

- Learners get an ample number of chances to practice the English pronunciation sounds.

This one-two punch allows multilingual learners to become increasingly comfortable with the movement of the tongue and the shapes their mouths and lips make as they build their oral language development skills.

One Ignite Reading student showed the power of this approach to his tutor late in the 2023-24 school year. A native Spanish speaker, the little boy told his tutor that he never thought he could learn to read until his tutor taught him the proper way to pronounce the sounds. “Now I can read the words right,” the excited young reader said.

2. Letter-Sound Correspondence

Another challenge many multilingual learners face is the association of those sounds with the letters of the English alphabet. This is not singular to MLLs — native English speakers also have to learn to associate sounds with letters in order to become fluent readers.

The challenges for English language learners show up differently in the classroom, however, depending on their stage of reading development in their home language.

1. Students Who Are Not Yet Reading Fluently in Their Home Language

Students who aren’t yet reading in their home language have yet to learn the association between sounds and letters — just like their English speaking peers. But these students also likely don’t have a strong foundation of English vocabulary or English sounds to help them on their reading journey, which means more scaffolded instruction is vital for learning.

2. Students Who Are Fluent Readers in Their Home Language

Those students who have already developed reading skills in their own language have the advantage of already understanding the relationships between symbols and sounds, but they have their own hurdles to overcome.

For example, students whose home language does not use the same alphabet as English or use a language that does not read and write from right to left — including the 130,000 multilingual learners whose home language is Arabic — need to learn a brand-new language structure.

Others may have to learn whole new sounds to associate with the individual letters.

Spanish speakers, who make up the largest segment of MLLs in the U.S., may be accustomed to associating the same sound with the letters b and v, only to find they’re used very differently in English.

How Structured Literacy Instruction Can Help

Once again, structured literacy instruction is designed in a manner that’s perfect to help multilingual learners master this new skill.

A structured literacy scope and sequence typically starts with the most basic phonics concepts — such as letter recognition and letter-sound correspondence — and builds on this to teach students how to blend those letter sounds to create words.

This gives multilingual learners an open door to learning the alphabetic principle of the English language, learning to correctly associate letters with the sounds they produce.

Some students who have English as a first language might not need a structured literacy approach to understand that we pronounce the word “pencil” the way that we do — it’s enough that they have heard the word pronounced this way countless times in their life.

But for a multilingual student who has just learned to say the word pencil, breaking it down and learning to pronounce the second syllable with a schwa sound helps them to recognize this is part of the structure of the word.

English language learners learn not just how to decode words but to also see the connections between decoding and understanding text.

3. Vocabulary and Background Knowledge

Imagine encountering an unfamiliar word as you’re reading. Using phonics skills, you identify the separate phonemes of each of the letters or letter groups in the word, then blend those sounds together to form a whole word.

When the letters come together, do you recognize what the word means instantly?

If you’ve heard it said aloud, you may.

In fact, many native speakers learn what most English words mean indirectly, through everyday experiences with oral language. This vocabulary knowledge then aids them in reading text.

If you don’t know the word’s meaning, you’re missing an important piece of the puzzle — comprehension.

That’s what happens for many multilingual learners. Even if they’ve developed foundational decoding skills, they struggle to understand what they decode because they do not yet have a broad knowledge of spoken English to draw from.

Often they’re still developing vocabulary knowledge (the meanings of specific words) as well as background knowledge (cultural understanding and lived experiences) that aid in word recognition.

How Structured Literacy Instruction Can Help

Using a structured literacy instruction approach, teachers can help their multilingual learners build up their vocabularies and background knowledge in two primary ways:

1. Word-Learning Strategy Instruction

Explicit instruction on a unit of language known as morphemes is part of any structured literacy approach, and it goes a long way in helping multilingual learners who are still making sense of word meanings.

Word prefixes, suffixes, and word roots are all examples of morphemes that appear over and over again throughout the English language.

These small units of English carry the same meaning no matter where they show up, so learning each of these morphemes arms kids with handy tools they can use to break down complex words into more manageable parts.

Take a look at the morphological composition of the word “uneventful”:

- Prefix — “un-” means “not”

- Base word — “event means “an important occurrence”

- Suffix — “-ful” means “full of”

When students can identify familiar morphemes like “un-” or “-ful,” they can then use that knowledge to infer meanings of unknown words, thus building their vocabulary. The long word “uneventful” is easier to understand when the reader already knows the “un-” portion means not and the “-ful” portion means “full of.”

2. Explicit Vocabulary Instruction

Of course, breaking down words isn’t always enough. If you aren’t familiar with the base word in “uneventful,” it’s still not going to do you any good to encounter it in text. You may be able to decode it, but it won’t have any meaning.

Explicit vocabulary instruction — delivered in a structured way — is crucial when working with multilingual learners. Teaching vocabulary across content areas will help students build their understanding of abstract concepts, multiple meaning words, and content vocabulary.

A Final Word on Teaching Multilingual Learners to Read

It’s hard to overstate the importance of learning to read fluently for all learners. It enables us to complete tasks as simple — but monumental — as reading road signs or a document at the doctor’s office. From an academic standpoint, fluent reading unlocks the door to learning across all subject areas.

Adopting a structured literacy approach to instruction is a vital step to ensure multilingual learners can access the English oral and literacy skills they need most to succeed.

Content updated February 14, 2025

Hero image via US Department of Education/Flickr