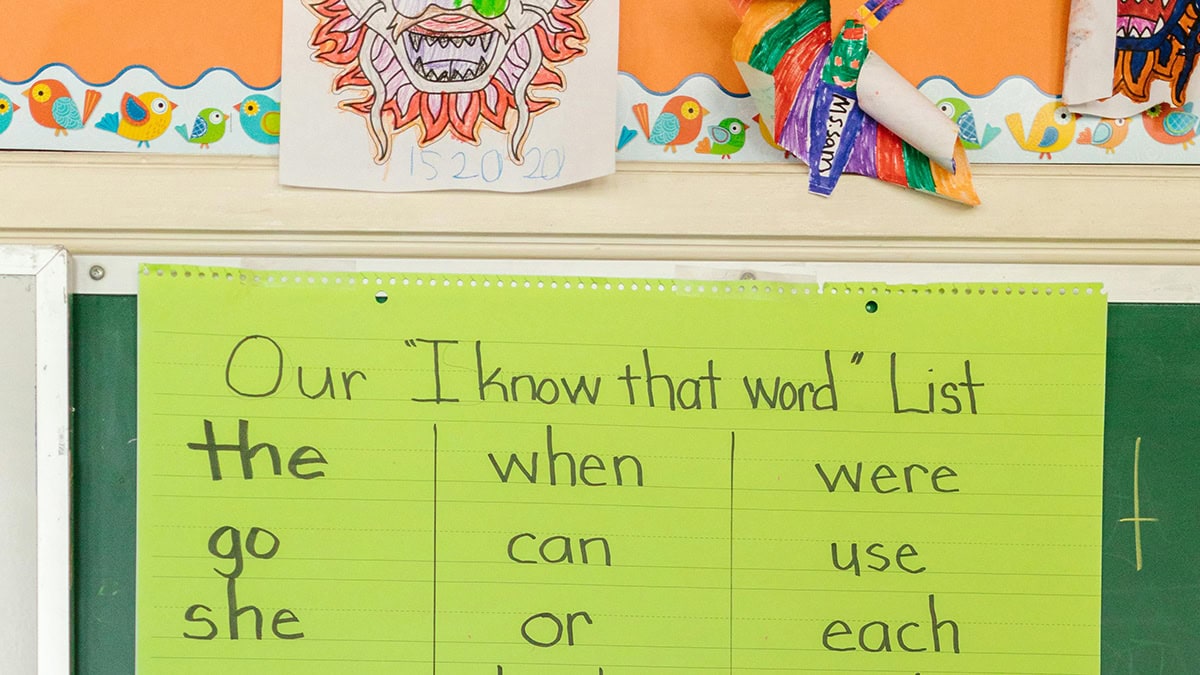

Sight words. Heart words. Instant words. Snap words. Whatever you call them, these so-called “irregular” words have played a major role in reading instruction in the last few decades.

But as Science of Reading-aligned curricula take over classrooms, is there still room for instructional methods that involve teaching students to recognize words on sight?

The answer isn’t a simple yes or no.

What Are Sight Words and Where Did They Come From?

This may feel obvious — sight words are short words like “girl” and “not” that students are encouraged to memorize so they will recognize them on sight.

The not insignificant problem with this practice is, of course, it doesn’t work.

In fact, the research tells us that it’s far more effective for teachers to call students’ attention to the parts of words that they know and do not yet know, rather than presenting words as whole entities.

So why is teaching students to memorize sight words so pervasive, and what — if any — place do high frequency words have in evidence-based instruction?

To answer the first piece of this, we need to go back to the time when sight words took hold in primary classrooms.

Dolch Sight Word List

Sight words’ popularity in classrooms is most often credited to one-time University of Illinois education professor Edward William Dolch, creator of the Dolch Sight Word list, and so-called Father of the Sight Word.

A proponent of the whole language method for teaching kids to read, Dolch published his first list of 220 words in a 1936 article that appeared in the Elementary School Journal.

Broken down into parts of the speech, the list of common English words was devoid of nouns, because Dolch believed teachers already “spent a great deal of energy” teaching their students to recognize the words that represent a person, place, or thing.

Dolch believed all 1st graders should be drilled in memorization of the sight words, and this would prepare them to recognize — and read — other words. As he said in his 1941 publication, Teaching Primary Reading, “To the beginner, ‘knowing the words’ means sight recognition. The child looks at the word form, and the word sound comes to his mind without his knowing either how or why.”

Should students struggle with reading any of the words on his list, Dolch called on teachers to print them on small cards and “flash” them over and over again until students could “read” them all.

While Dolch did leave room for some phonics instruction, his instructions were far from effective. Dolch believed phonics instruction should:

- Not be taught until 2nd grade

- Be based on teaching students to recognizing pattern in words they already know and relating those patterns to other words

Fry Sight Word List

A second name we associate with sight word is that of Rutgers University professor Dr. Edward Fry.

In the 1990s, Fry created his own list of words — known as Fry’s Sight Word List, naturally — with 1,000 of what he called “instant words,” all of which he said students needed to memorize in order to become proficient readers.

Fry’s giant list was culled from more than 87,000 words that appear in the The American Heritage Word Frequency Book, a reference created in the early part of the 20th century to represent the most frequent words appearing in more than 1,000 texts representing reading requirements and recommendations in grades 3–9 in the U.S.

Sight Words vs. The Science of Reading

Through the Science of Reading, we know that the best way to teach kids how to read is by giving them a set of phonics rules, then teaching them to use those rules to decode new words, connecting their letter-sound correspondences and mapping them into memory.

However, schools throughout the United States are still teaching hundreds of words — words like those found on the Dolch and Fry lists — through rote memorization, rather than taking a grapho-phonemic approach.

Why do we continue to treat these high-frequency words as a special, excepted class?

Perhaps it’s time we revisit how sight words are being taught.

What if schools taught a more complete set of phonics rules, giving emerging readers a broader set of letter-sound correspondences and empowering them to decode thousands more words — including sight words?

Educator and reading researcher Denise Eide, the founder of Logic of English, thinks it’s time for a change — she advocates for applying the same methodology we use for teaching “regular” words to high-frequency words.

Her body of work—full of straightforward rules and more than a few aha moments—explains that there is a more complete set of rules that can help emerging readers decode nearly all the words on lists like — those words we currently teach as exceptions.

Here’s what she has to say about the current state of “sight words” and how we can improve students’ fluency by teaching them to use the letter-sound analysis of the letters in irregular words.

What Is Incomplete Phonics?

Right now, educators largely teach what Eide calls “incomplete phonics.” In essence, that means that there are many rules of the English language that are not being taught at all, rules that would better help students decode words.

For example, based on these incomplete rules, an emerging reader would likely sound out the word “is” as /i/ /s/ instead of /i/ /z/. But “s” also says /z/ in several other words, including “his,” “as,” and “was” — all words included on the Fry sight words list of 1,000 commonly used words.

If this s/z correspondence only occurred a handful of times in English, there’s an argument to be made for teaching it as an exception. But according to Devin Kerns’ Phinder, “s” says /z/ 43 percent of the time. So even though there’s a near-even split between “s” saying /s/ and /z/, most curricula are still teaching kids that “s” only says /s/.

If we were to teach students these additional rules, they would be able to sound out many of the words currently deemed “sight words,” rather than forcing them to rely on rote memorization.

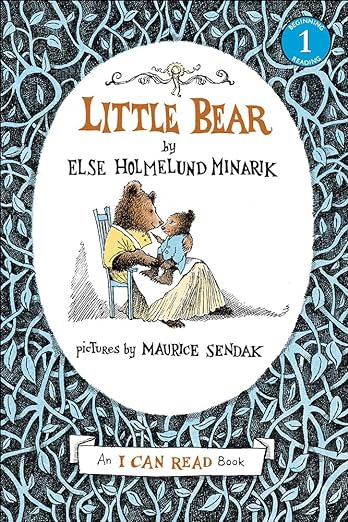

Lately, Eide has been exploring what happens when we don’t teach a complete set of phonetic rules and then give kids an early reader book like Little Bear by Else Holmelund Minarik. Using the incomplete rules, 46 percent percent of the words on the page are “exceptions,” which means they can’t be sounded out using the phonics rules that are typically being taught.

The word “bear,” for example, breaks the “if two vowels go walking, the first one does the talking” rule. So we teach kids to resort to using first letter, last letter, picture and context cues because our phonics rules don’t hold up.

But if we taught students that “ea” can say two additional sounds (those found in “bread” and “steak”), the reader would have the tools to decode the word “bear,” thereby building automaticity and improving overall reading fluency.

Incorporating Sight Words Into “Complete Phonics”

While many people in the Science of Reading world know some pieces of these more complete phonics, and some curricula incorporate many of the rules, they still aren’t broadly being applied to those high-frequency sight words.

As Eide sees it, taking that step is a matter of looking at the language and seeing the rules that have been there all along.

Her approach is to “look at how frequent these [exception-to-the-rule] phonograms or letter-sound correspondences are in the high-frequency words, the 100 words that make up 50 percent of everything kids read and write. Because if we say these words are exceptions, we’ll be saying that a lot as kids read a text.”

By some counts, 30–40 percent of these high-frequency words are exceptions to phonics rules. But, as Eide’s work suggests, if you teach a more complete set of phonics rules, only 5 percent of them are actually exceptions.

The Future of Teaching Sight Words

Whether you call them high frequency words, sight words, snap words, or heart words, as you can see, these words are not a special class.

As Eide’s work shows, “they use the same rules you need to explain all the words in English,” which means we can — and should — apply a phonics approach to teaching students to read these words.

Eide’s approach has the potential to help kids and multilingual learners alike properly decode a huge number of additional words.

It could have long-term benefits for spellers of all skill levels. It could help dispel the idea that the English language is full of exceptions and questions we’ll never answer. And it could all but eliminate the need for separate word lists or much memorization at all.

These are ideas that districts, educators, literacy advocates, teacher trainers, and anyone interested in developing successful readers should consider as we look toward a more complete approach to phonics instruction—and a more clear-eyed approach to “sight words.”

Where to Start: Implementing Complete Phonics in Your School District

Eide suggests that the shift toward a more complete set of phonics rules has to start with a shift in mindset—moving from a belief that the English language is full of exceptions to the belief that there are answers.

“My goal when I speak to educators who are new to this is to challenge this idea [that many phonics questions have no answers],” Eide explains.

“In science, when a kid has a question, we don’t tell them that something we don’t know is an exception to the laws of physics. We say, ‘I’ll look that up.’ If we can begin the cultural shift of saying, ‘I don’t know, but I’ll look it up,’ and find the phonics rules that apply, that’s a big step.”

As “no one owns the copyright to the English language,” Eide’s Logic of English publishes the phonograms and spelling rules they teach for free on their website.

When this information is available to everyone, the Logic of English team’s thinking goes, any district or educator can gain and teach a more complete understanding of phonograms and letter-sound correspondences.

About Ignite Reading

Ignite Reading delivers 1:1 online tutoring to students who need extra support in learning to read. Our expert tutors teach students the foundational skills they need to become confident, fluent readers by the end of 1st grade.

With a team of literacy specialists and highly trained tutors, we provide daily, targeted instruction that quickly closes decoding gaps, so students can successfully make the transition from learning to read to reading to learn.